Killing didn’t bother Wheeler. Not this late in the day. Maybe in the war he felt something; regret, shame, sadness, but he couldn’t be sure. He only remembered the fact of it; that he had picked up his rifle and kept himself alive at the expense of others.

His head was always clear. Clear before, clear after. It wasn’t coldness as such. Once a woman had called him a fatalist, and he clung onto that. He didn’t think they had a name for it, but sure, fatalist was just about a perfect way to say it. When they put names, addresses and money in an envelope for him, he pocketed it. So long as he could kill someone, then it was their time to die.

It fit how he saw the world, before the war even. He had seen that man, trapped at the road’s edge by the weight of an upturned car. The people who had given up hope for him and stayed hoping for themselves when fire started, running away while he called out and cried. There were minutes between them all knowing it was too late and them all actually seeing it. Wheeler had sat on his bike and heard that man ask ‘Why?’ with a despair he’d heard a hundred times since. Back then he knew there was no such question as why. Not for dying.

But his body was never as clear on these things as his mind. It seemed to burn up more of him that he liked when he killed and he always felt spent and a little sick afterwards. Even if he’d done as little as line up one shot, just as soon as the man at the other end expired, Wheeler’s insides would go to smoke. He felt like bottled vapour and he never got used to it. Other men he’d seen at work sometimes got shakes, and Wheeler knew he was lucky not to get those. They cost men dearly, he’d seen that much. But all the same, he would have done anything to turn to solid rock when he felt ghosts inside.

Which is why he was lucky to sit across from the runaway.

Wheeler had driven north for about an hour and then stopped at a place to eat. He knew he had to eat, but there was nothing inside him but sickness and smoke and finding an appetite for grease or meat or salt sweat tastes was a trick and a half. He sat at the counter with the menu propped in front of him, not really reading, just making busy until he’d talked himself into ordering. It was then he saw the boy. A scruffy, skinny kid who had the collar of a shirt and two jackets turned up. He came with a kit back and rolled up blankets and it was Wheeler’s guess that he had run away from home. Maybe he wanted to join the Army or maybe he didn’t. The kid looked healthy enough, he can’t have been on the road all that long. Wheeler watched him, but the boy never noticed. The boy was too confident to care and Wheeler was too good to be caught. Wheeler knew the boy wasn’t trouble, but he seized him up like he was. The kid probably carried a switchblade, had a good reach and was likely quick and fierce. He had been in fights before and might even have won some of them. He was too thin to take any long punishment, and he was handsome, which meant he would back away if he could. Wheeler had no intention to fight him, these were checks he ran on anyone, the same way he knew the waitress would kick better than most men, and if the short order chef had a knife, Wheeler had better have a gun.

If Wheeler did have to fight, if this kid wanted cash, or the cops drew up outside, Wheeler wouldn’t be fit. Not with the ghosts.

The runaway ordered a Chocolate Malt. Wheeler found himself talking. Just into open air at first.

“Chocolate Malt?”

“What’s that pops?” the kid came back. Something dry about his voice.

“Nah, nothing.” Wheeler said. “Just haven’t had one of them since I was in short pants.”

“You looking to have some of mine?”

“No, son. I’m not looking for trouble either. Just talking.”

“Talking a whole lot about Chocolate Malt.”

“Guess I am. That all you’re having?”

“I got a lot of walking.” By now the shake had been set in front of him, and he took a long, indulgent slug of it and wiped his mouth on his sleeve. “And not much cash. These things put the hunger back, you know what I mean? Feels like a meal, and tastes a damn sight better than some slop and cheese.”

“Smart.”

“Not enough not to be where I am. But maybe more than most.”

“Maybe.”

Something about it fit with Wheeler and he turned to the waitress, who was sizing them both up, and ordered. “I’ll have what the kids having.”

“You gonna pay for mine?”

“If I did, kid, you’d think something about me that just aint true.”

“Guess so.”

“And you’d do well do go without that kind of help, whether offered or asked for.”

The waitress smirked at this, which was something Wheeler didn’t like. The kid didn’t like it either and drank up in silence before leaving. Wheeler had wanted to say good luck, but whatever happened to the kid now was nothing to do with him. Instead he watched the waitress until she understood.

Wheeler took it all as an omen. The milkshake was his talisman. The thing had gone down thick and smooth and had dowsed fires and filled up everywhere he was empty. It was like a meal, and more. The ghosts disappeared and Wheeler was back on the road, repaired.

Monday, 21 July 2008

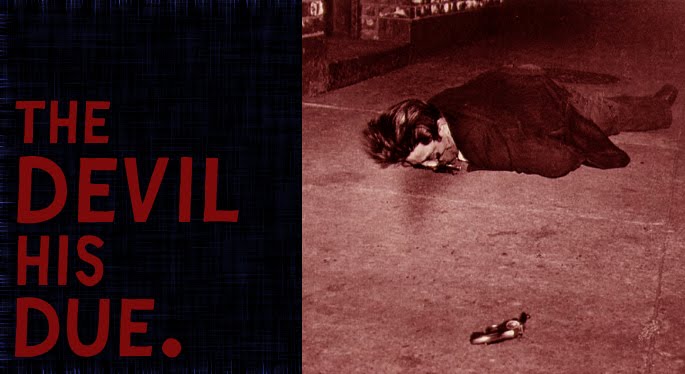

The Devil His Due. Chapter Two: The Borrowed Man

They had communicated with a man they thought was called John Teak. But he was not. He looked like John Teak in as much as he had a blank, flat face on a square head sat atop a slender body, with broad shoulders. John Teak was slightly taller, but that was fixed by lifts in the shoes. John Teak had smaller hands, but you could trust that very few would ever pick up on this. John Teak had short salt and pepper hair, and though this man was born blonde, he was salt and pepper today, and had been for four weeks, parted to the left, the same way John Teak did. This man had narrower eyes, and one of them did not contain the slight smudge of pigment in the right eye that made John Teak’s look like a drop of milk in black coffee. This was regrettable, but not problematic, as none of his employers had even met the real John Teak.

John Teak, the real John Teak was sunk somewhere in Florida. His head and his hands apart from the rest of him, but deep in the black stink of swamp all the same. This new John Teak had his wallet and his car, and four of his suits. He also had John Teak’s pipe, though he did not use it.

In New York they shook hands with him. They took him at his name because they lacked imagination. He felt a flicker of disgust at this, behind a door he seldom ever opened. Then the flicker was gone. It was fine, he reasoned. If these people had imagination, they would not need him. If people did not disgust him, he would have to think differently about his work.

John Teak, the new John Teak, cut a length of electrical cord from a lamp and curled either end around either fist. He curled the rest around the neck of Antonio Ceres.

When Mr. Ceres had stopped kicking, and his hands dropped, John Teak let go. Then he took from an envelope in his pocket $1,000 in $20 bills - the same sum Ceres had allegedly taken just to write down the address of the now late Archie Vander. The money was curled into a short pipe of paper and, as per New York’s orders, pushed into the open mouth of the dead man.

When the police later questioned the hotel staff on duty that day, they did not remember the man in the blue suit who had crossed the lobby in full view of most of them.

After this, the man pretending to be John Teak would have to pretend to be someone else. A routine precaution. At the airport he would watch for a man, a dull man of a similar build, hopefully alone and hopefully close to his looks. John Teak had lasted for three assignments and would have to retire. The man that travelled back to Geneva was yet to be found.

He called New York, and they made him hang up so they could call him back. He listened to what they had to say, which was panicked, excitable, noisy. They forgot to even thank him for the service he had just performed. Now they wanted to bully him into something else. He called Geneva, which was out of the ordinary, but New York had insisted he did. Geneva spoke coolly, without rushing into things, but the message was the same. His contract with New York was to carry over into this new item. They would pay him the same rate again, and then once more on top.

If he could kill a man called Wheeler.

John Teak, the real John Teak was sunk somewhere in Florida. His head and his hands apart from the rest of him, but deep in the black stink of swamp all the same. This new John Teak had his wallet and his car, and four of his suits. He also had John Teak’s pipe, though he did not use it.

In New York they shook hands with him. They took him at his name because they lacked imagination. He felt a flicker of disgust at this, behind a door he seldom ever opened. Then the flicker was gone. It was fine, he reasoned. If these people had imagination, they would not need him. If people did not disgust him, he would have to think differently about his work.

John Teak, the new John Teak, cut a length of electrical cord from a lamp and curled either end around either fist. He curled the rest around the neck of Antonio Ceres.

When Mr. Ceres had stopped kicking, and his hands dropped, John Teak let go. Then he took from an envelope in his pocket $1,000 in $20 bills - the same sum Ceres had allegedly taken just to write down the address of the now late Archie Vander. The money was curled into a short pipe of paper and, as per New York’s orders, pushed into the open mouth of the dead man.

When the police later questioned the hotel staff on duty that day, they did not remember the man in the blue suit who had crossed the lobby in full view of most of them.

After this, the man pretending to be John Teak would have to pretend to be someone else. A routine precaution. At the airport he would watch for a man, a dull man of a similar build, hopefully alone and hopefully close to his looks. John Teak had lasted for three assignments and would have to retire. The man that travelled back to Geneva was yet to be found.

He called New York, and they made him hang up so they could call him back. He listened to what they had to say, which was panicked, excitable, noisy. They forgot to even thank him for the service he had just performed. Now they wanted to bully him into something else. He called Geneva, which was out of the ordinary, but New York had insisted he did. Geneva spoke coolly, without rushing into things, but the message was the same. His contract with New York was to carry over into this new item. They would pay him the same rate again, and then once more on top.

If he could kill a man called Wheeler.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)